|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

I've gotten a few requests for my opinion about the race between China and the US to get to the moon, asking "who will win?"

It turns out that the Chinese lunar program is interesting, especially where they have made different decisions than Apollo or Artemis.

If I'm feeling obnoxious, I'll just point to this picture from Apollo 11, but that's not really the question that people are asking, so let's look at the two programs...

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=2807488182831257

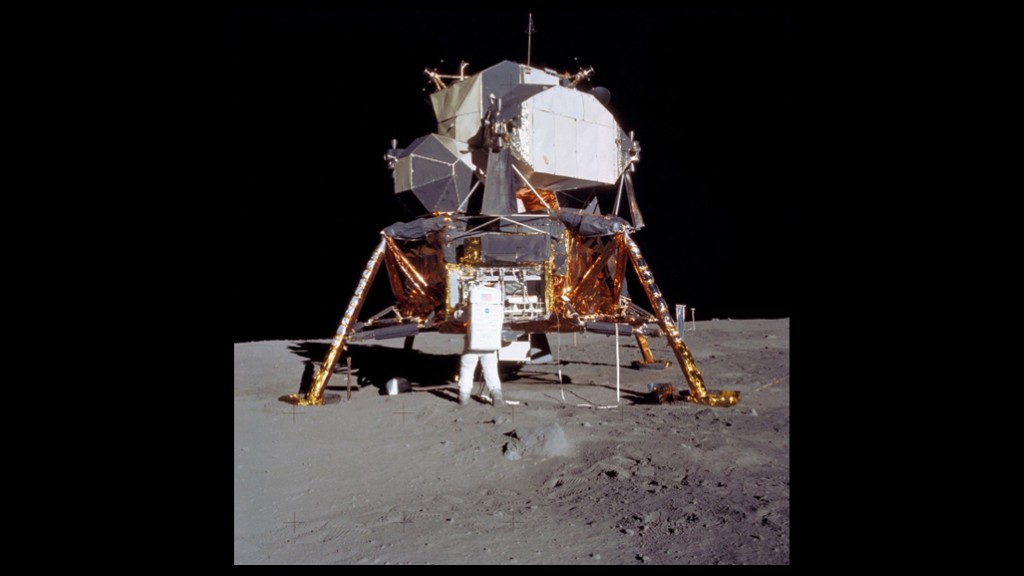

China announced their lunar exploration program in January of 2004. I'm going to apologize up front for my poor pronunciation...

The program is named Chang'e (chowng-e) after a woman who flew to the moon to protect her husband and stayed there as the goddess of the moon.

All of the lunar probes are simply numbered.

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/jaGGupIlQ3s

1 and 2 were orbiters, flying in 2007 and 2010.

3 was a lander with a rover named Yutu (yuu-toe) after the pet rabbit of Chang'e and launched in 2013. 4 was a backup for 3, and was flown on a separate mission in 2018 after the success of the earlier mission.

5 was a sample return mission flown in 2020, returning 1731 grams of lunar samples back to earth.

And 6 flew a sample return mission to the far side of the moon and returned 1935 grams of samples to the earth. It also carried a mini-rover.

7 is expected to fly in 2026 to explore the lunar south pole for resources, and 8 in 2028 to explore in situ resource development and utilization.

China has a nice exploration program. It's steady with increasing difficulty, and it's important to note that they have a perfect record with landing on the moon. They have made that look easy.

Moving onto the US, NASA had a not-well-known program called the lunar precursor robotic program, designed to use robotic spacecraft to prepare for future missions to the moon.

The first mission included the Lunar Reconnaissance orbiter, and the lunar crater observation and sensing satellite, designed to explore a region of the lunar pole by crashing the spent centaur upper stage into it.

The other program mission was the lunar atmosphere and dust environment explorer.

NASA also performed lander missions, but they were NASA funded and run by commercial partners under the commercial lunar payload services program, usually known as CLPS.

Peregrine 1 from Astrobotic flow in January of 2024. It developed a propellant leak and was ultimately directed to burn up in the Earth's atmosphere.

IM 1 from intuitive machines soft landed on the moon in February of 2024, but tipped to 30 degrees.

Blue Ghost from Firefly successfully landed in proper orientation in January of 2025.

Intuitive machines tried again with the same lander for their IM-2 mission in February of 2025 , but that spacecraft ended up on its side on the moon.

It's tough to compare the achievements of the two countries as the programs are very different - the Chinese program is mostly about technological development and is fully run by the government, and the NASA programs are either pure science programs or tests of commercial space in a lunar context.

But it's hard to miss the 4 successful Chinese landers and the single successful US lander.

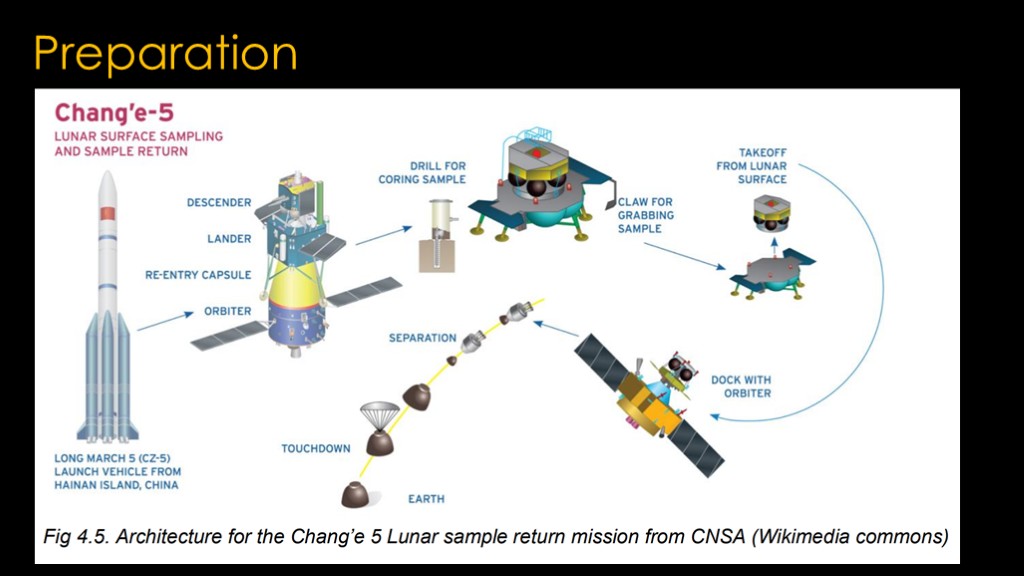

What I don't think is adequately appreciated is the complexity of the Chang'e 5 and 6 architectures and how closely they resemble Apollo.

The full stack is launched by a Long March 5 heavy lift rocket, one that can send about 9 tons to the moon.

The payload consists of an orbiter, a reentry capsule and a lander. The lander lands, collects a sample, puts it in the ascender (it's mislabeled as "descender" on this diagram), and the ascender lifts of, docks with the orbiter/return capsule which journeys back to earth and the return capsule reenters and touches down. It's the Apollo architecture on a smaller scale and without people.

The crewed landing obviously requires crewed spacecraft, and China is in a bit of a transition.

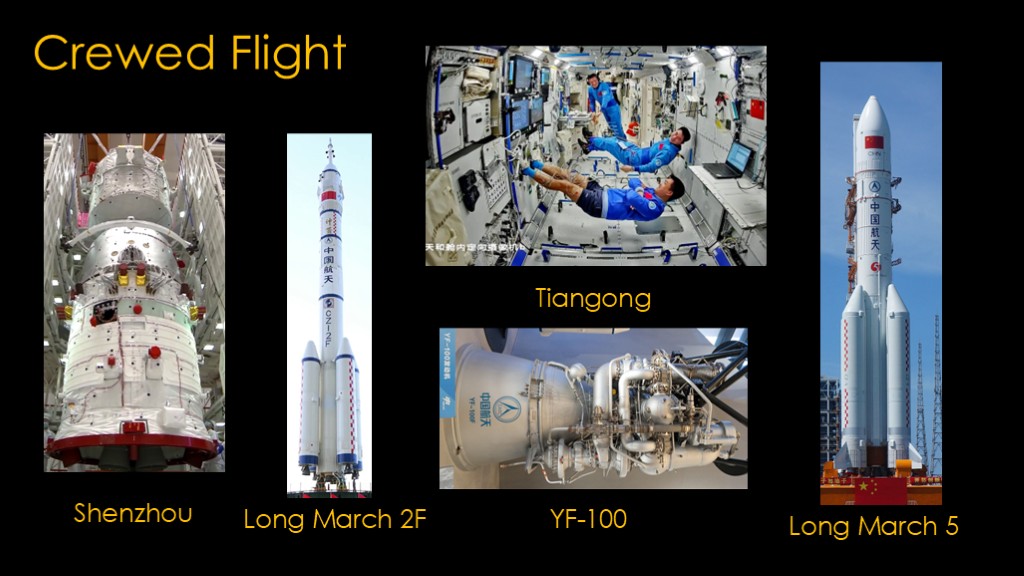

China currently flies astronauts on their Shenzhou (shen-joe) spacecraft. It is based on the Russian Soyuz but is a bit larger and more modern.

It has carried crew 15 times and has no reported failures.

It launches on the Long March 2F rocket, a medium lift rocket with a payload to LEO of about 9 tons, or about half of what a Falcon 9 can carry. The Long March is derived from the DF-5 ICBM and uses storable hypergolic propellants.

China has assembled a space station named Tiangong, or "heavenly palace", and they are currently on their 9th crewed expedition.

The space station modules were lifted using the Long March 5, a modern heavy lift launcher. It uses an architecture similar to Ariane 6 with a first and second stage that both run on liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, or hydrolox. The long march 5 uses liquid fueled boosters burning RP-1 kerosene and liquid oxygen - or kerolox - rather than the solid boosters that Ariane uses. Each booster uses two YF-100 engines, essentially a copy of the high-performance Russian RD-120 staged combustion engine.

The covers the current low earth orbit hardware. The lunar architecture needs 3 new pieces of hardware.

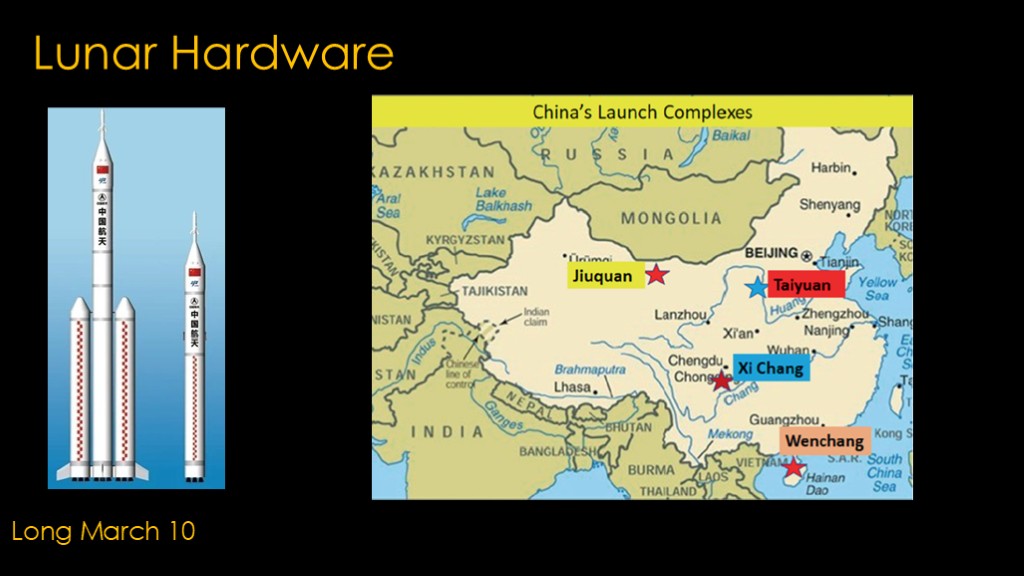

The first is a super heavy lift rocket, the long march 10, which has a projected payload of 70 tons to low earth orbit and 27 tons to the moon. That's a little less than the SLS block 1 payload.

Architecturally, it's like a big Falcon heavy, with two 5 meter boosters next to a 5 meter core, each with 7 YF-100K engines burning kerolox. There's a second stage also burning Kerolox, and a third stage burning hydrolox.

A launch pad and support systems for Long March 10 is under construction at Wenchang launch center in southeast China.

Long March 10 also has a 10A variant with a single core first stage that is designed to be reusable.

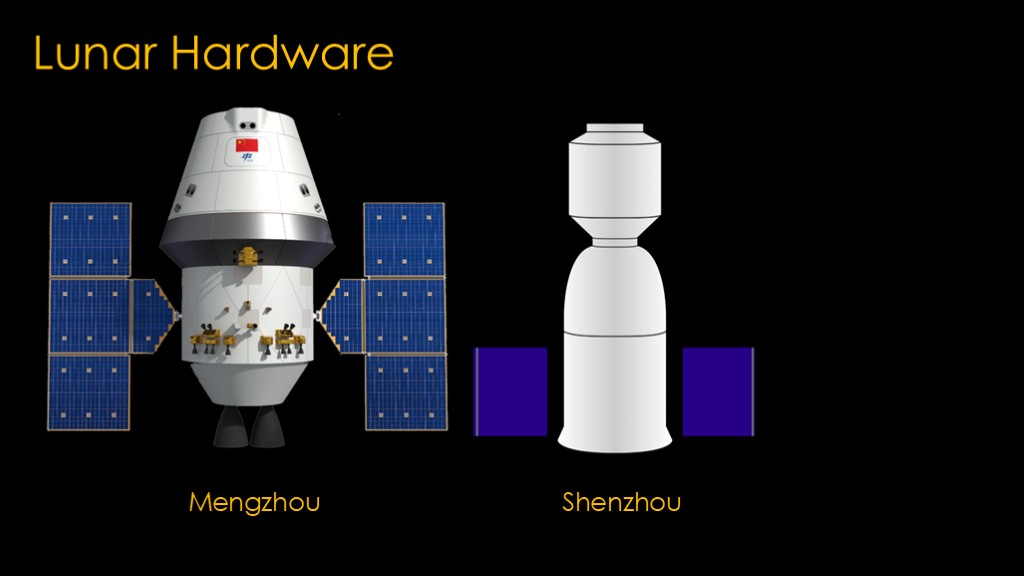

There is a new lunar capsule named "Mengzhou" (meng chjoe), or "dream castle".

It is a significantly bigger capsule than the existing Shenzhou (shen-joe) capsule, and is designed to function both as a lunar capsule and as a low earth orbit capsule.

The original Orion capsule design was also intended to do that.

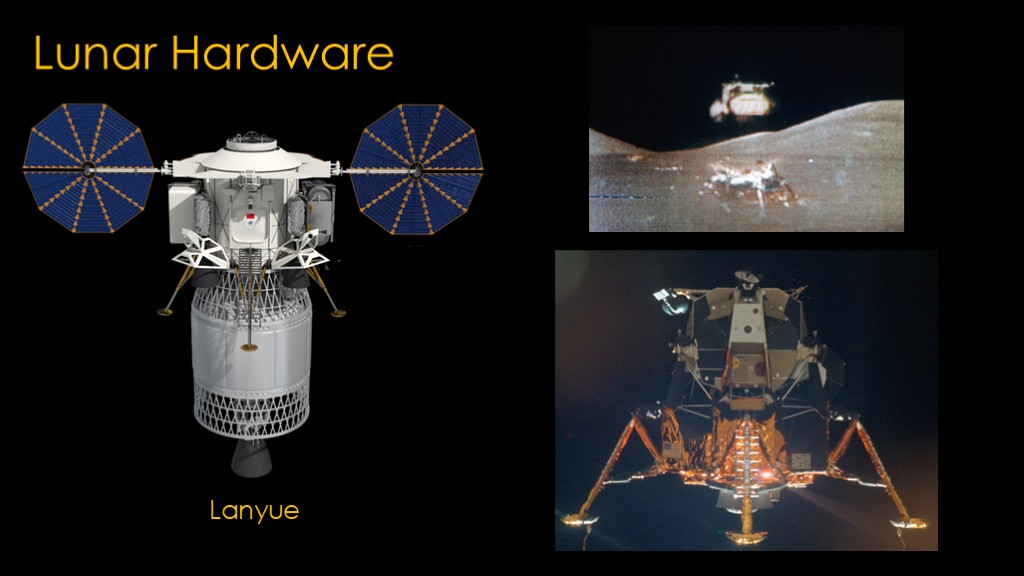

They also have a lander, named Lanyue (lan yeh), or "embracing the moon".

Lunar landers are very hard to build. Apollo solved that by landing the full lunar module and then leaving the descent module on the lunar surface.

Lanyue has an interesting twist on that approach. Instead of making a full system that can land on the moon, it has a descent service module that does the bulk of the work getting to the surface of the moon, and that service module is discarded near the surface and the lander does the rest of the work to land. It's an elegant solution, and results in a two-person lander that is about the size of the Apollo ascent stage.

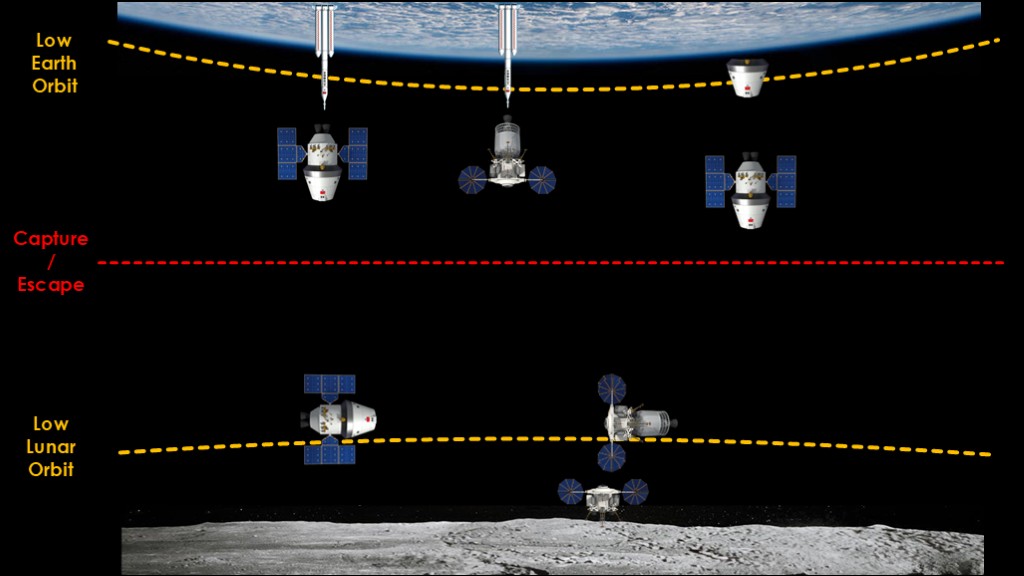

We don't have full details on their lunar architecture, but here's how I think it might work.

A long march 10 launches the Lanyue lander and service module towards the moon, and the service module brakes into low lunar orbit.

A second long march 10 launches the Mengzhou capsule with two astronauts towards the moon, and its service module brakes into low lunar orbit.

The two spacecraft dock, and the crew transfers into the lander.

The lander descends, discards the service module, and lands. After the lunar surface mission is over, it boosts back to low lunar orbit where it docks with the capsule. The crew boosts back towards earth and as it nears earth, the capsule and service module separate and the capsule returns and lands.

On to the US program.

It's complicated and will take a bit of time to explain.

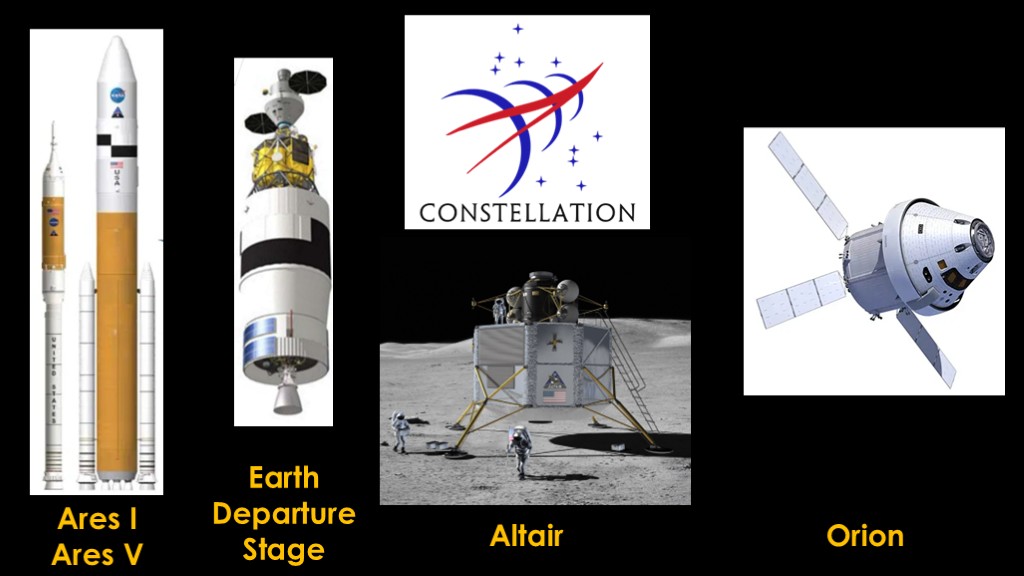

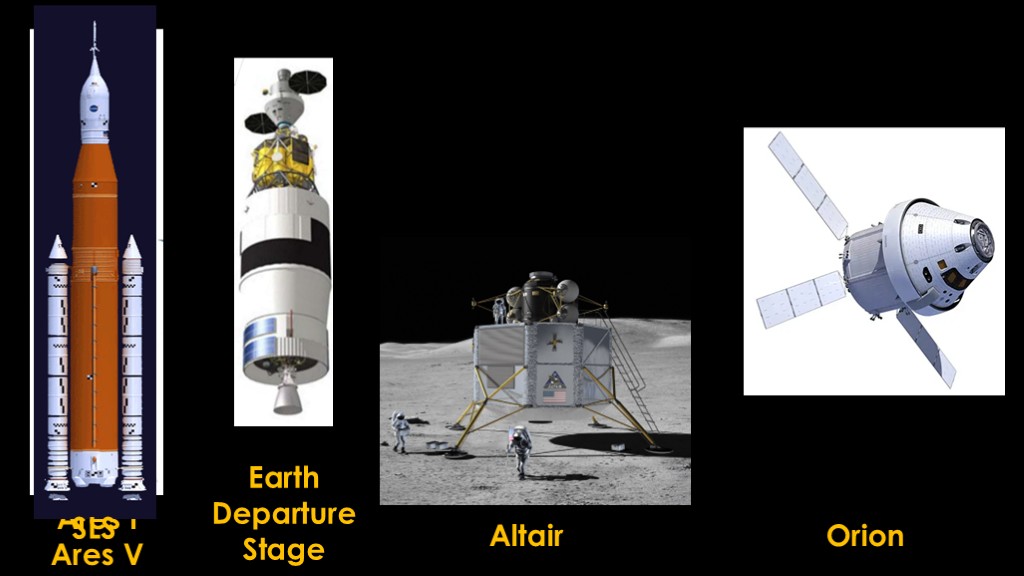

NASA's first post-Apollo architecture for the moon was named constellation.

It featured two new spacecraft, a lander named Altair and a new capsule and service module that would later be named Orion. Both were bigger than Apollo, and that would require a new rocket, or in this case two new rockets - the Ares I to lift the Orion capsule and the Ares V super heavy lift rocket to carry the lander.

The Ares V wasn't up to sending Altair and Orion to the moon by itself, so an Earth Departure Stage was added. It would perform the same function as the third stage on the Saturn V.

Constellation was cancelled in 2010 after a detailed review of NASA's plans concluded there was no budgetary environment in which they could be completed.

This cancellation did not make Congress happy, as the Ares launchers were shuttle derived and as such were good at sending money to the contractors and NASA centers that had worked on shuttle.

Congress made their opinion very clear with the NASA authorization act of 2010, which said (read)

The Ares 1 and 5 would be merged into a single less capable launcher named SLS and Orion development would be continued.

Congress deleted both the earth departure stage and the lander.

SLS and Orion were an architecture without a defined mission.

The Obama administration proposed a mission to rendezvous with a deep space asteroid, and then move onto Mars missions. Neither of those missions were practical with just SLS and Orion.

Congress had concluded that the benefits that they derived from 30 years of shuttle missions could mostly be obtained by just building a big rocket and capsule without a mission.

That lasted for a half decade until late 2017 when the Trump administration decided that the US should return to the moon and build a permanent US presence, and the Artemis program was born.

But there was a big problem.

SLS and Orion could make it into a lunar orbit and back home, but NASA had no way of getting astronauts down the lunar surface and back.

That turns out to be a tall order.

The Orion that was part of constellation had a relatively big service module, but after the cancellation of Constellation there was no clear mission for Orion and NASA wanted to save money.

The current service module is designed and provided by the European space agency as their contribution to Artemis.

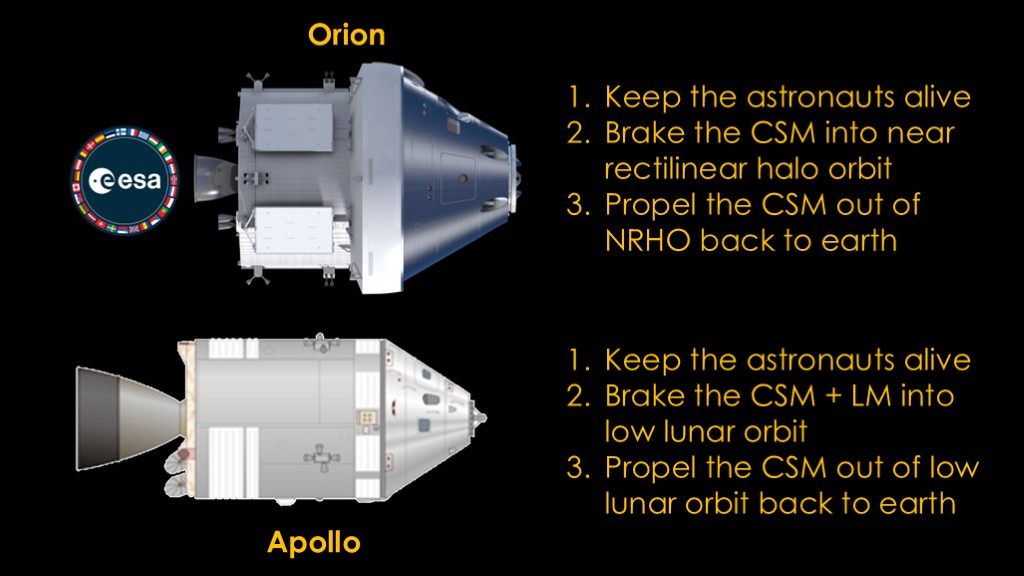

If we compare the Orion to the Apollo command and service module, the comparison is pretty obvious. Orion has a big capsule and a small service module, and Apollo has a smaller capsule and a big service module.

For Apollo, the service module had 3 big jobs.

First, it needed to keep the astronauts alive during the mission.

Second, it needed to slow down the command and service module plus the lunar module so they could enter low lunar orbit.

Third, it needed to propel the command and service module out of low lunar orbit back to earth.

To do the second and third meant it had to carry quite a bit of propellant.

The orion capsule weighs about 60% more than the Apollo one did, and the service module carries less propellant. That means it can't do the same things that apollo could do.

It can keep the astronauts alive. It can put the capsule into lunar orbit, but not the low lunar orbit but an easier-to-get to near rectilinear halo orbit, and it can't bring a lander along with it. Then it can get out of that orbit and go back to earth.

Artemis needs some other way to get a lander to lunar orbit so that it can take astronauts to the surface and back.

Could we use SLS to carry a lander that can do the job?

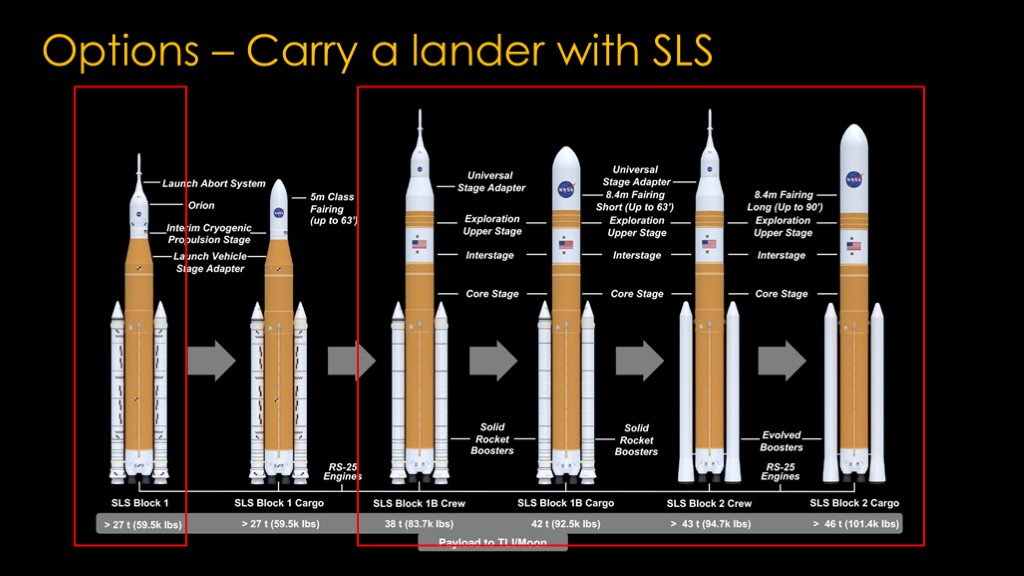

The first - and current - version of SLS - block 1 - can only toss orion towards the moon. The later block 1b and block 2 versions can toss an extra 15 or 19 tons to the moon.

The Apollo lunar module was 15-16 tons, so that might work - except that the lunar module could not get from near rectilinear halo orbit down to the surface and back - it simply doesn't have the fuel.

And block 1 was already late and the bigger versions were years away.

And even if that worked, Orion doesn't have the oomph to put a lander into orbit.

You could do what the Chinese were planning and use multiple SLS rockets, but they cost at least $2 billion a pop and the suppliers are only set up to make 1 per year right now. And the second stage used with block 1 is no longer available and the one planned for block 1b is years behind schedule.

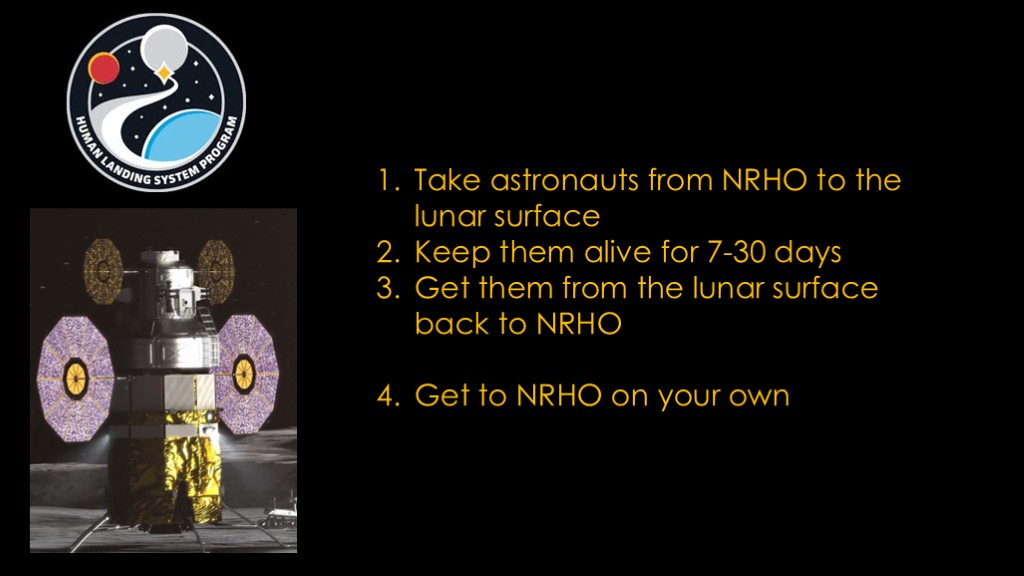

The was why the human landing system program was created.

The requirements were simple.

(read first 3)

Those are pretty hard.

And since SLS and Orion can't carry you, you also have to get your lander from earth to lunar orbit.

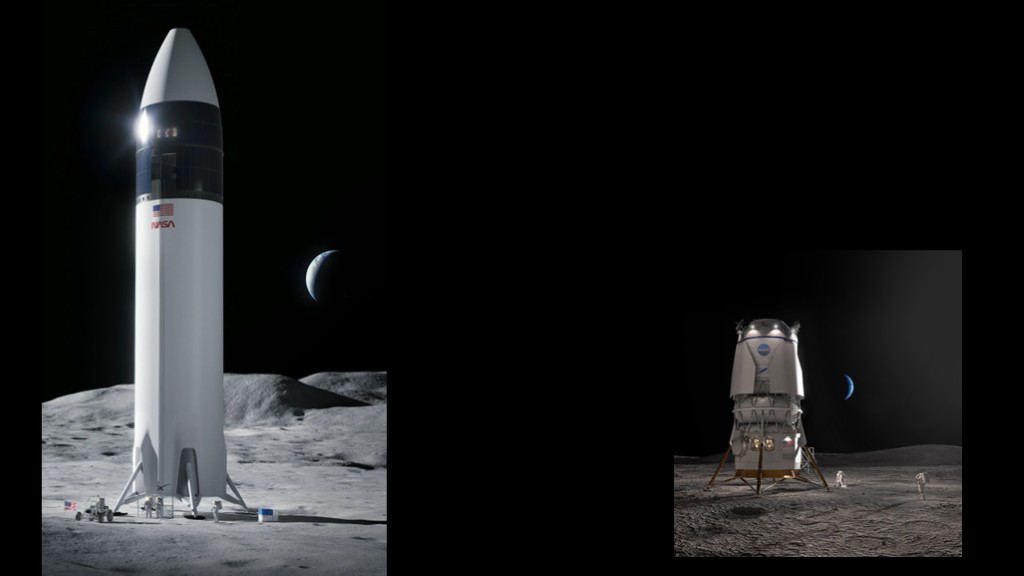

SpaceX won the competition for the human landing system and got the Artemis 3 and 4 missions, and Blue Origin later won the continuing lander contract and got Artemis 5 and 6.

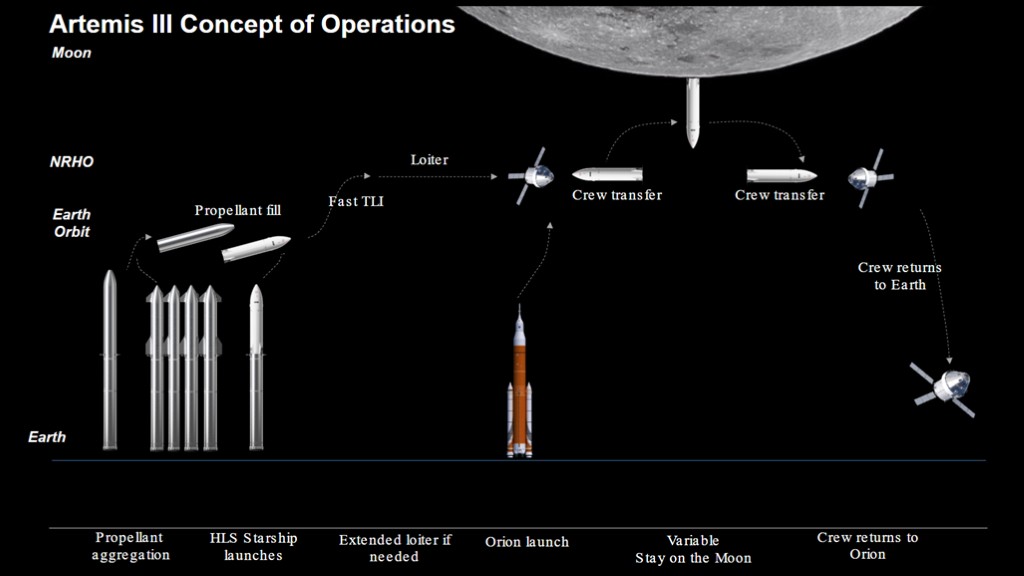

To do this with starship requires that the lunar lander starship be refueled in low earth orbit, with at least 10 starship tanker flights.

This has never been done before, and was widely derided as impractical.

That's not just a problem with the SpaceX approach.

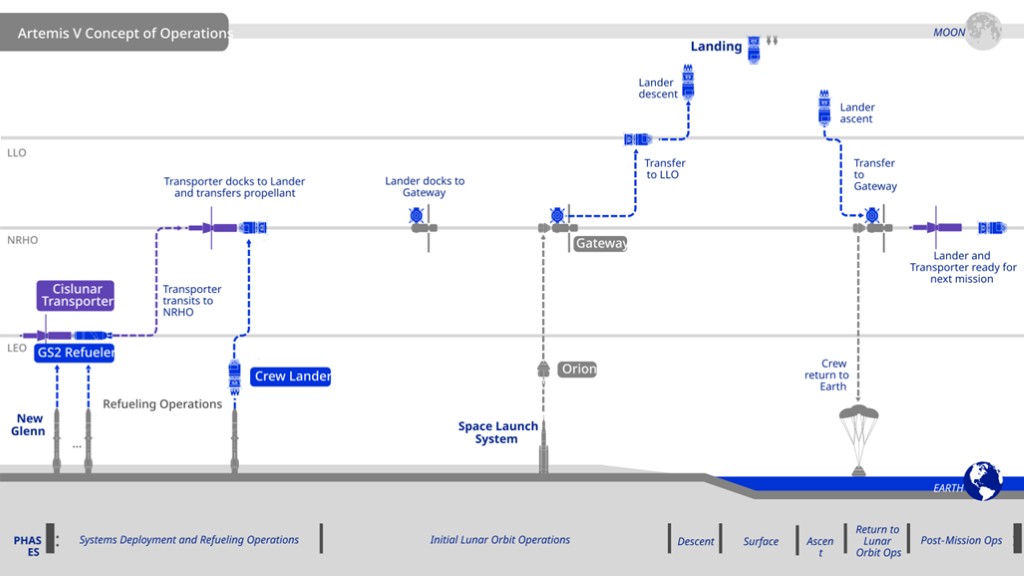

Blue Origin's approach also requires the launch of a refueling depot and then an unspecified number of refueling missions, with the final refueling in lunar orbit.

The difficulty of what NASA wants to do pretty much makes refueling a requirement.

Getting a lander from the earth to the surface of the moon and back to near rectilinear halo orbit is a much more challenging problem than getting a capsule in lunar orbit and back home, and the Starship HLS lander wasn't chosen until April of 2021, roughly 10 years after the start of SLS development.

What is the status of the programs?

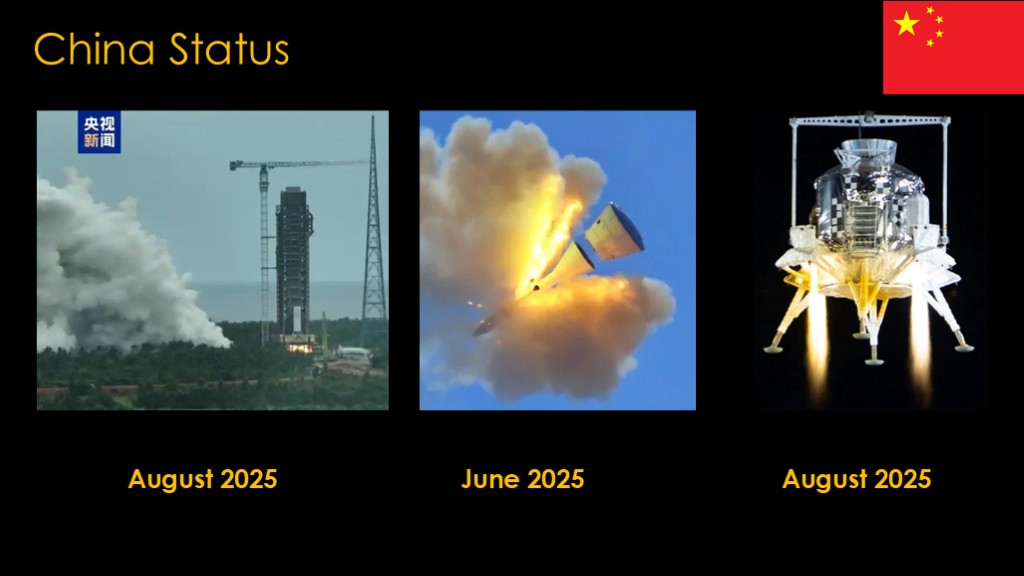

China appears to be making good progress, but it's important to remember that we are probably not seeing the underlying issues the program is working on

Long march 10 underwent its first static fire on august 15th of 2025. China generally does not publish future plans, but I expect the full vehicle to fly in the next few years.

The Mengzhou (meng chjoe) spacecraft completed an orbital test flight in 2020 and recently completed a pad abort test.

The Lanyue (lan yeh) lunar lander recently completed a series of both landing and ascent tests, supported by a simulator that gave it appropriate lunar gravity.

China also has their lunar spacesuit and lunar rover under development, but their status is less clear as they are not tested in the open.

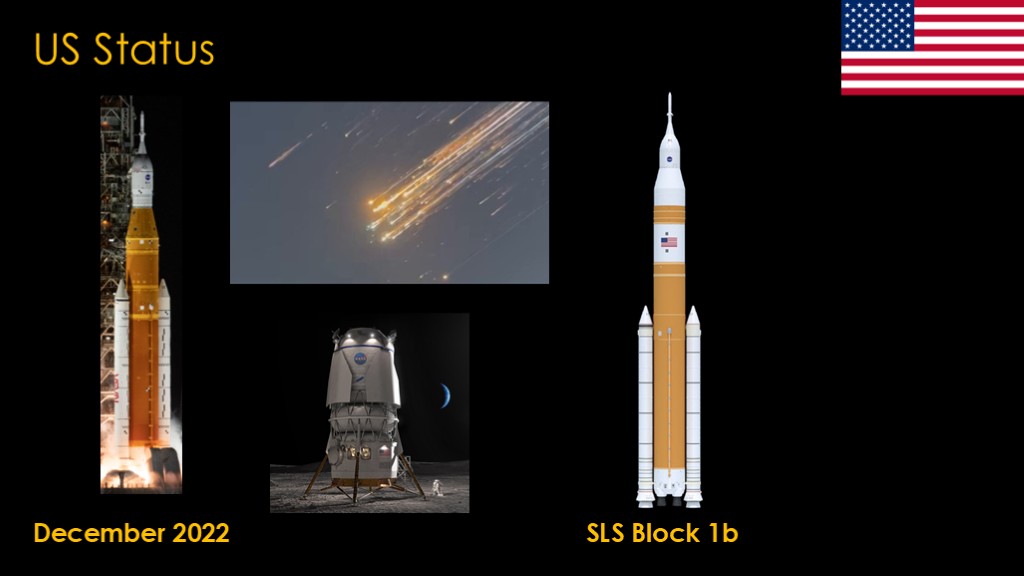

On the US side, Artemis 1 flew an uncrewed flight in December 2022, and encountered significant issues with the heat shield on the Orion Capsule. Artemis 2 is currently scheduled for April of 2026, though NASA is currently ahead of schedule and might launch earlier.

SpaceX is currently having issues with the block 2 version of starship and it's not clear when those might be resolved. The lunar startship is on hold until starship is ready.

The status of Blue Origin's Blue Moon is unclear. They are currently manifested on the Artemis V mission with an estimated date of March 2030.

Artemis 3 will use the last SLS block 1 rocket, which uses a modified delta rocket upper stage that is no longer available. Future missions will require a new second stage. The current plan is to use the Exploration Upper Stage on the block 1b rocket , but that also requires a new mobile launch structure. Both the upper stage and the launch structure are very delayed.

So, who is the likely winner?

Right now I think it's very hard to tell, but I do have a few thoughts...

The first is that it's not clear that it's actually a race. In the 1960s the US was sprinting quickly to meet President Kennedy's goal to complete the mission by the end of the decade, and the Russians were doing absolutely everything they could to keep up.

Today, the Chinese have a very well-planned and executed program, but they have a timetable and they are sticking to it.

The US is kindof sortof committed to the moon as long as congress is happy with where the money goes and the President is behind it.

It could go either way, and I'm not convinced that it matters in a meaningful way.

I think there is a more important question.

Who is on the moon for the long term?

China is planning to create an international lunar research station, with their first missions starting in 2031. They are cooperating with Russia's ROSCOSMOS, though it's not clear what Russian will be able to do as their space program is a shadow of its former self.

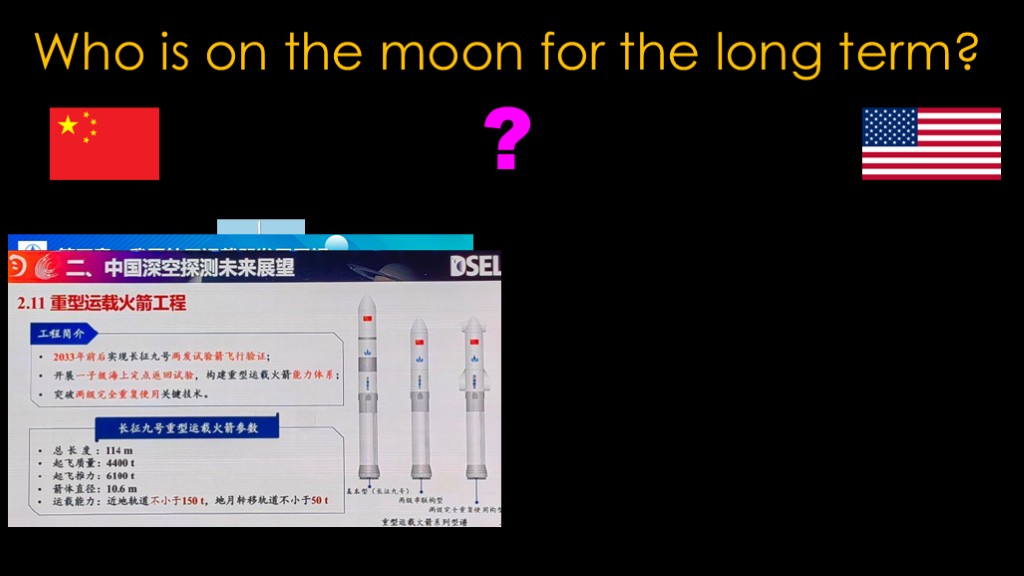

Establishing such a base is impractical using the long march 10, and China has been working on the long march 9 to play that role.

It's gone through a number of variations, but the current plans look pretty familiar, with a methalox booster using 30 full flow staged combustion engines and a few different upper stage designs, one that looks a little like starship.

It would not be surprising if the change in architecture delays long march 9 more.

For the US, the near term plans are to fly an SLS/Orion mission roughly once a year and to use the extra capacity of SLS block 1b and block 2 to build the lunar gateway along the way.

They have longer term plans for what is known as the Artemis Base Camp.

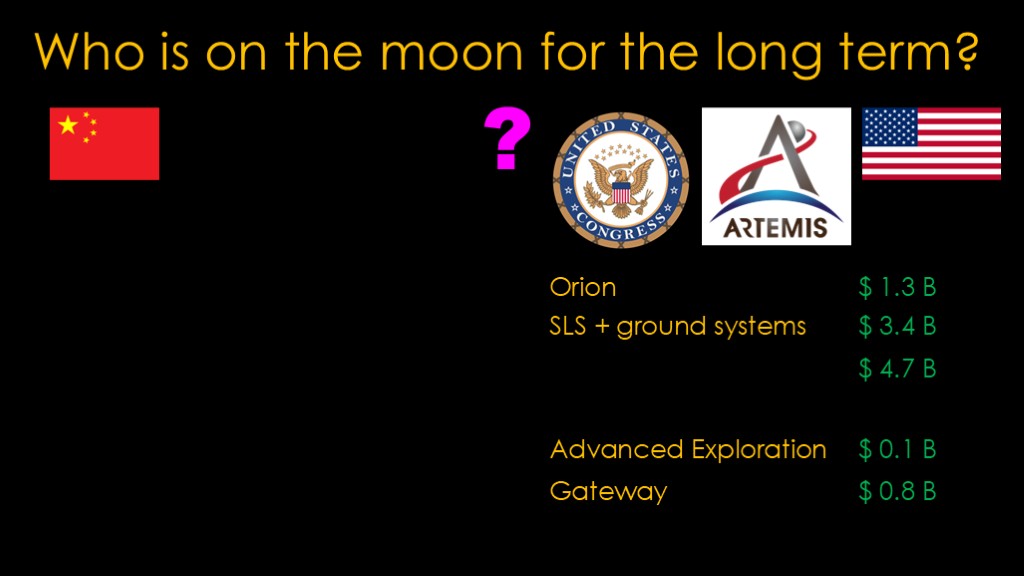

The problem with the US lunar program is that - while support for NASA is general widespread - the congresspeople who make decisions around NASA programs love the status quo because it is a jobs and reelection program for them, and that's especially true for SLS and Orion.

Looking at 2023 actual costs, Orion cost $1.3 billion, SLS + the ground systems to launch it - primarily the new mobile launcher for block 1b - cost $3.4 billion, for a total of $4.7 billion. SLS and Orion have been coasting along at about $4 billion per year for the past decade, and it's going to take a powerful force to stop that, and if that happens, it's not clear that the money previously allocated to them would be allocated to other NASA programs.

NASA is spending a small amount on Advanced Exploration Systems - roughly $150 million a year - and that covers a large range of technologies that might be required for a lunar base, but no actual base hardware.

By comparison, the lunar gateway - another one of those status quo programs - costs about $800 million a year.

If Orion and SLS stick around and the NASA budget is flat, it's hard to see how NASA might pay for all the infrastructure for the Artemis base camp.

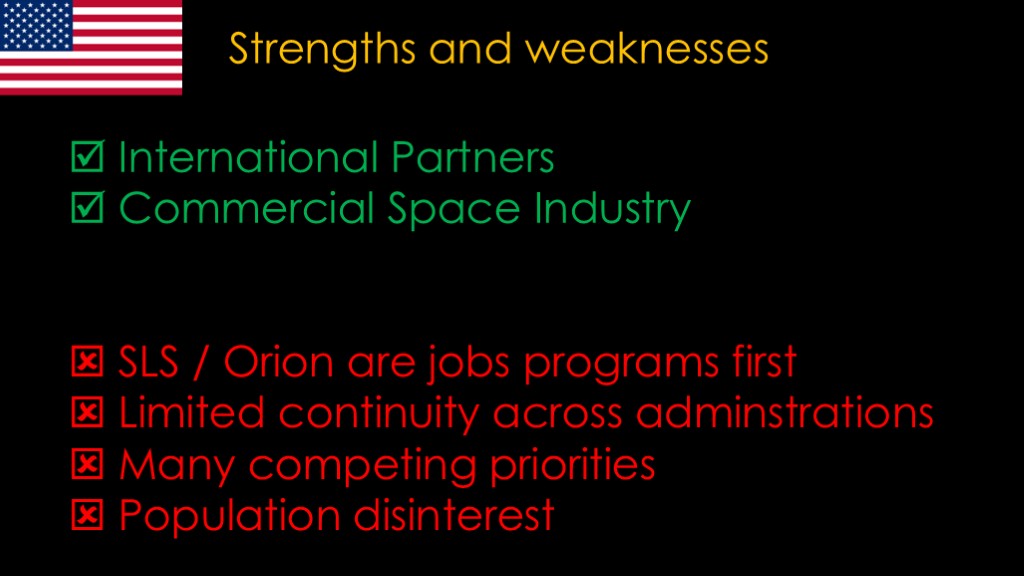

Let's look at some strengths and weaknesses

China has.

The US has an established network of international partners and a robust commercial space industry.

I expect the Chinese to win the moon in the long term.

For that to change, congress will need to cancel SLS and Orion *and* allocate that money to programs that leverage commercial companies. I don't think that is likely with what we are currently seeing.

If you enjoyed this video, here's your song of the day...